For some, hydrofracking means more jobs, more fuel and more money.

For others, it means temporary jobs, environmental damage and decreased property value.

Those are the two views of the economic potential of the controversial gas-drilling method called hydrofracking, or fracking.

“For state and local governments, oil and gas are cash cows,” said Timothy Considine, an economics professor with the University of Wyoming‘s School of Energy Resources and a leading expert in natural gas reregulation. Considine is a supporter of fracking and sees it as a plus for New York State.

But Sarah Eckel, legislative and policy director at the Central New York/Finger Lakes Citizens Campaign for the Environment office, is a strong critic and skeptic of fracking. “In the Rust Belt, which is where we live, we really know the price of an industry coming in, using our resources and leaving a legacy of toxic waste behind,” said Eckel.

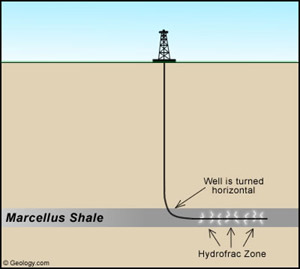

At the center of this dispute is the Marcellus Shale. The Marcellus Shale is a black shale formation that extends from Ohio and West Virginia to Pennsylvania and the Southern Tier and Catskill regions of New York. Along the Pennsylvania border and in the Delaware River valley the shale is 7,000 feet or more below ground level. In the Finger Lakes region, it lies near the ground surface.

Hydrofracking is the process of pumping water, other fluids and a material like sand into a well under high pressure to create fractures in dense rock, like shale. The fractured shale allows more gas to be released. Hydrofracking the Marcellus Shale would involve using more than one million gallons of water per well.

As of now, hydrofracking is not allowed in New York state. The state government is awaiting findings from a Department of Health review of the practice before it makes an official decision on allowing it.

For the economy, fracking raises these issues:

- JOBS

In a study for the Manhattan Institute of Policy Research, economist Considine of Wyoming University argues that Western New York and the Southern Tier would gain more than 15,000 new jobs if fracking is allowed. Those would include construction of the wells and in industries that use natural gas.

But Mike Dulong, staff attorney at Riverkeeper, a clean river advocacy group based in Westchester County, disputes that the jobs created by hydrofracked wells will benefit the state. Many of the jobs the proponents claim will be created in New York, he said, will be filled by out of state residents imported by drilling companies to New York.

“There’s an influx in people that would come in to the state,” he said, adding that these people would place an economic burden on the state and local governments to accommodate the newcomers. “That cost comes immediately, but any benefits that the town or municipality can hope to get from fracking, tax-wise, would not come immediately. It would take a year or two years,” Dulong said.

- Money

Allowing fracking in the Marcellus Shale areas would help many New York counties, said economist Considine. He describes the wells in Pennsylvania as almost Middle East-like. “That generates a lot of money,” he said.

If the state decides to allow fracking, said Considine, the government should also examine its tax system. New York should look to Pennsylvania as an example, he said. Ideally, Considine said, the state should “have a regulatory agency that’s funded by fees on the industry.”

In Pennsylvania, where an impact-fee law was passed in February 2012, every gas-drilling well in the Marcellus Shale region must pay a yearly levy based on gas prices and the Consumer Price Index. Of that fee, 60 percent stays in the counties and municipalities where the wells are located while the rest is channeled to state agencies. Pennsylvania collected over $204 million in impact fee revenues for the 2011 year, according to the newly-launched Public Utility Commission’s Act 13 interactive website.

But Riverkeeper’s attorney Dulong says to expect similar gains in New York is premature. One of the biggest potential problems with allowing fracking is with bonding and insurance requirements, he said. As things stand now, the bonding and insurance requirements needed to drill in New York are very minimal, he said. These fees are what would go toward cleanup costs, if a drill site is contaminated. In New York, he said, if drilling companies go bankrupt or out of business, the cost of remaining toxic cleanup is funneled to individuals.

These accidents are something to be almost counted on, said Eckel, of Citizen’s Campaign for the Environment. When it comes to high volume drilling, Eckel said, the chances of mistakes are multiplied. “The fact of the matter is this is an industry that is controlled by humans,” she said. “You can have the most perfect technique. But at the end of the day there’s still a human standing behind it making it happen so you’re going to have accidents, you’re going to have problems.”

- Environment

Bryce Hand, emeritus geology professor at Syracuse University, argues that fracking’s benefits to New York outweigh potential risks. “Any major industrial operation will have costs, environmental costs,” Hand said. But fracking for natural gas, he said, will provide the community with a cleaner fuel that produces far less carbon dioxide emissions than oil or coal, something he believes will help fight global warming in the long run.

“I say if you offer me a fuel that provides half as much carbon dioxide – the main greenhouse gas – that produces twice as much energy, for the same amount of CO2 production, I would say, ‘For crying out loud go for it,’” said Hand. Hand predicts that eventually the drilling will be allowed. No matter how long it takes, he said, “The gas will be there.”

But opponents call for a longer-term look at choices. Eckel, of Citizen’s Campaign for the Environment, points to Onondaga Lake as an example. The cleanup there has taken years and has divided communities, she said. Said Eckel: “We’re still living with that legacy of toxic waste.”

(Heather Norris is a graduate student in magazine, newspaper and online journalism.)

-30-