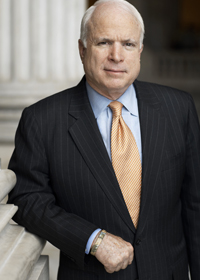

When President Ronald Reagan wanted to keep American forces in Lebanon for 18 more months, newly minted Republican Congressman John McCain – Navy veteran, son and grandson of admirals, prisoner of war – had a one-word answer:

No.

“He’s a reluctant warrior. He understands the human cost of war in a way few people do. Folks who have military experience — especially the kind of military experience he has — are very reluctant to commit troops into harm’s way.” (Francine D’Amico, director of Undergraduate International Relations program at Syracuse University)

As D’Amico and other foreign policy experts explain it, McCain’s foreign policy views and efforts in Congress strongly reflect his experiences as a military man and POW. And those experiences also would likely shape his actions as president, if McCain, the Republican, beats his Democratic opponent Barack Obama.

The foreign policy experts suggest that McCain’s experiences make him hesitant to put troops into harm’s way. But once military force is exerted, McCain doesn’t want to pull out unless a clear victory is at hand. He’s also been dedicated to causes like granting rights to prisoners of war.

Like his father and grandfather, McCain was a career Naval officer, retiring as a captain. He is one of the most celebrated American prisoners of war. As a young Naval aviator, he was shot down over Vietnam, where he spent five years as a captive of the infamous “Hanoi Hilton” prison. He has written of being tortured by his captors.

McCain has been in Congress since 1982, when he was elected to the House of Representatives from Arizona. In 1984, he was elected to the Senate. In his quarter of a century in Congress, McCain’s foreign policy positions follow some general trends. His record reveals that gaining his support to send troops abroad isn’t easy to come by.

In an e-mail interview, foreign policy expert Michael O’Hanlon of the Brookings Institute writes: “On the one hand, McCain is a big believer in American values. His personal story speaks of reconciliation and open-mindedness – given his support towards Vietnam during the process of normalization in the mid-90s. On the other hand, he is also quite resolute in his commitment to prevail in military conflicts once initiated, as we have seen in the Balkans, in Iraq, and in Afghanistan.”

In 1999, for example, during NATO’s campaign to stop Slobodan Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing campaign in Kosovo, McCain supported a full on engagement including the deployment of ground troops. He told The New York Times that the U.S. must stand up to Milosevic. If not, he said, “Then we will be vulnerable to many challenges in many places.’

In 1991, McCain also strongly supported the first Persian Gulf War when Iraq’s Saddam Hussein invaded neighboring Kuwait. McCain commended then-President George H.W. Bush for pushing Saddam Hussein’s forces out of Kuwait and he agreed with the first president Bush that U.S. troops should not then have invaded Iraq.

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, McCain strongly supported the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan to topple the Taliban, crush Al-Qaeda, and find Osama Bin Laden. His support to expand the Bush administration’s war on terrorism also led him in 2003 to vote for the invasion of Iraq. After years of slow progress in nation building, McCain became one of the main proponents of the 2007 troop surge in Iraq, which many believe has greatly stabilized the country.

In contrast, McCain has stood against using military force and supported diplomacy numerous times in his political career. During his first year in Congress, for example, his vote against then-president Ronald Reagan’s plan to commit U.S. troops to a military effort in Lebanon was one of McCain’s first influential efforts to shape foreign policy. At the time, he called the proposed plan an ill-defined mission, saying in a speech, “The longer we stay in Lebanon, the harder it will be for us to leave. We will be trapped by the case we make for having our troops there in the first place.”

Similarly, in 1993, when then-president Bill Clinton wanted to expand U.S. efforts in Somalia and begin nation building in the war-torn country, McCain opposed the proposed mission. In a speech, the McCain called it “an unfocused mission that lacks an objective and exposes them to further harm.”

Professor Francine D’Amico of SU says that McCain’s selection of when and where to use force is grounded in his time serving in the armed forces.

“He — like many other military folks — says ‘Look, when there’s a clear mission and it’s clear that military force will accomplish the goal in mind — that’s reasonable. But when there are a range of options and military force is just one of those options and it’s not clear that military force will accomplish whatever the goal is — I’d rather not get it started.'” (Francine D’Amico, director of Undergraduate International Relations program at Syracuse University)

His time as a prisoner of war in Vietnam also clearly still echoes in his stance on current issues — like supporting legislation to ban the use of torture tactics against POWs. McCain has also been vocal against the torture of prisoners kept in Guantanamo Bay, even calling for the base to be shut down.

Bill Smullen is a retired military officer and now director of SU’s national security studies program. He stresses that McCain believes in the Geneva Conventions. The Conventions are a set of international treaties protecting the rights of soldiers and non-combatants in war.

“McCain goes back to his five-plus years in confinement and recalls that, recognizing that he was not granted those rights. He wants to make sure that he encourages and requires that others do.” (Bill Smullen, director of the National Security Services program at Syracuse University)

The election is November 4th.

For Democracywise, I’m Boris Sanchez.

(Boris Sanchez is a senior with dual majors in broadcast journalism international relations.)

-30-